After a lonely year, high-energy Camp H.O.P.E. in the West End helped children reconnect.

- Six-week summer camp for first through eighth graders, plus high schoolers

- 75 students attended camp this summer, taking part in activities ranging from reading, math, and mindfulness, to cooking, dancing, sports, and more

- Offered learners a much-needed reintroduction to socializing after a year of isolation

By Faith Schantz, Contributing Writer for A+Schools

It started with six kids on a living room couch. Keysha Gomez and her husband, John Paul Gomez, had noticed there wasn’t a lot of out-of-school-time programming for youth in their community. “So we started doing what our cultures teach us to do,” she says, referring to her Jamaican background and her husband’s Gambian background. They invited children into their home to cook, play chess, and dance. When more and more children came, “we realized that there truly is a need and that we were filling it unintentionally.”

That was in 2010. In 2014, H.O.P.E. for Tomorrow (standing for “Helping Ourselves Produce Excellence”) was officially born with nonprofit status and Keysha Gomez as executive director, in Pittsburgh’s West End.

H.O.P.E. for Tomorrow filled another need this past year, when schools shut down due to the pandemic. With help from A+ Schools and funding from the United Way and other partners, the organization sponsored a learning hub from February through June, providing a safe space for about 40 students overall to attend virtual school while their parents worked. The organization re-opened the hub in August when Pittsburgh Public Schools delayed its starting date.

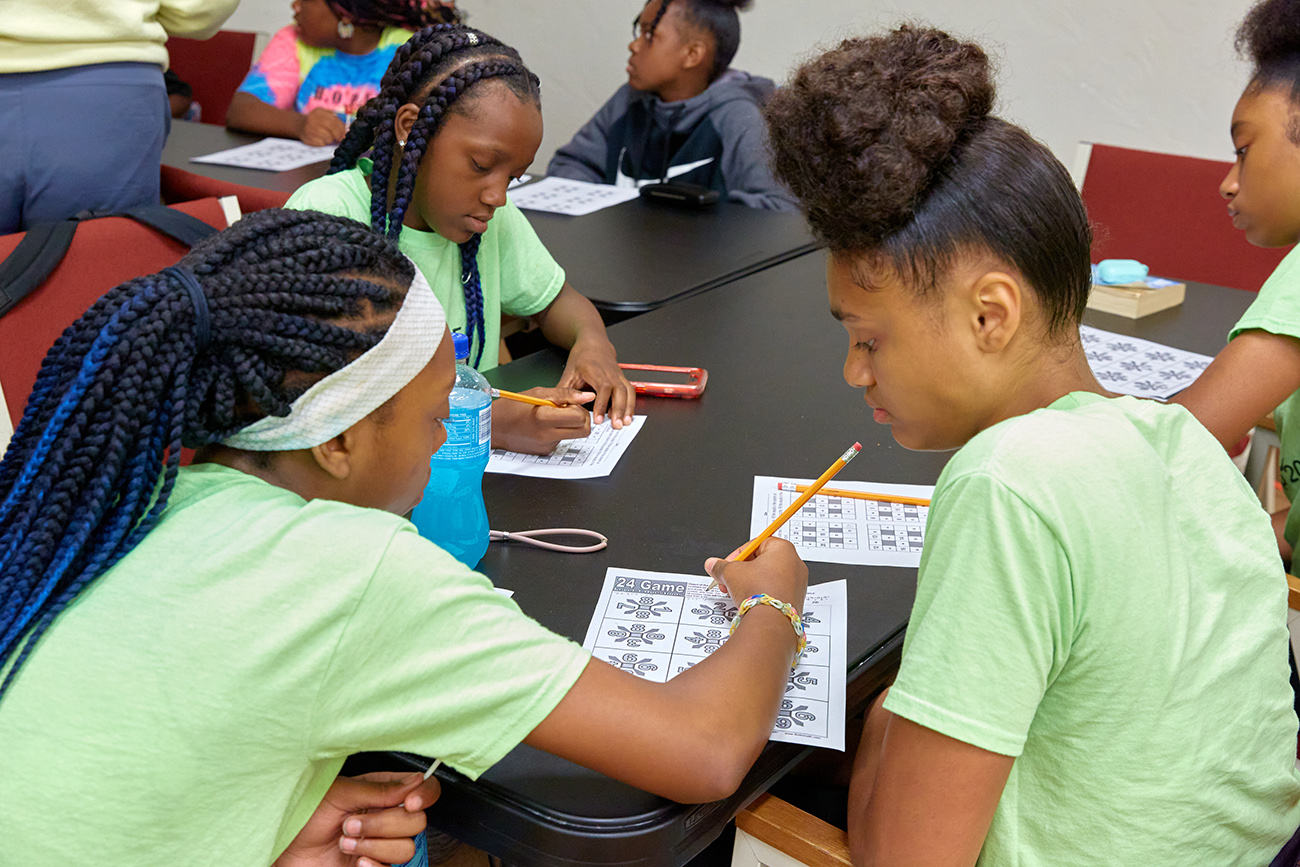

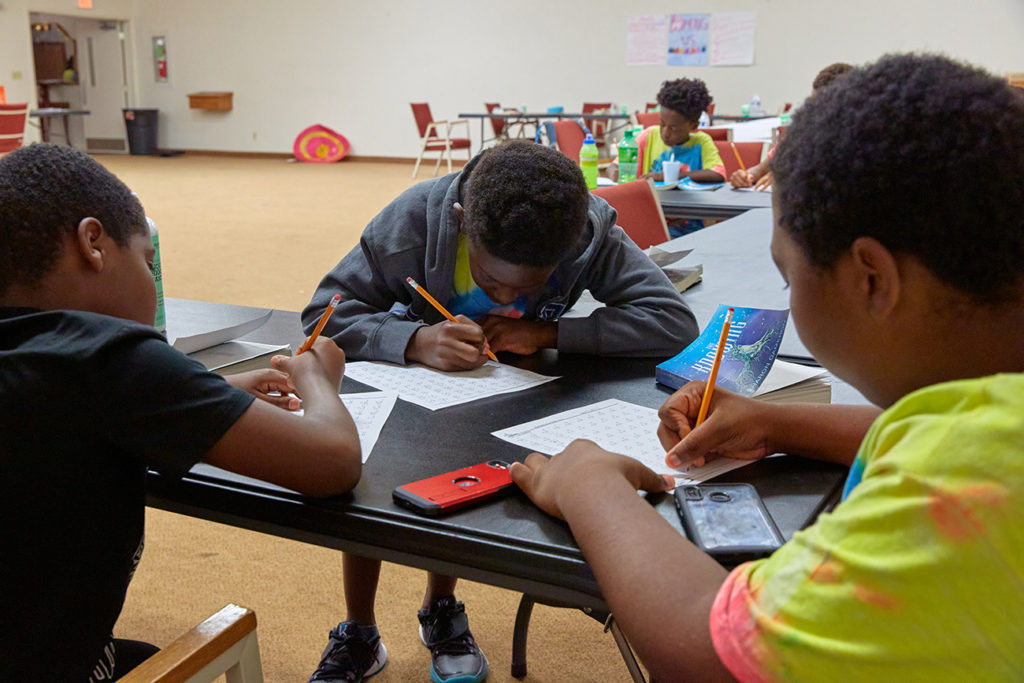

The learning hubs bookended Camp H.O.P.E., which served 55 first through eighth graders and 20 high school students this summer for six full weeks. The day started with a bang: music blasting as children arrived, matching their high energy, followed by the camp’s traditional chants. After breakfast, younger students read silently for 20 minutes and practiced math skills, which could involve relay races or games of catch to help them memorize facts. Three days a week they learned life skills—including character development offered by the Macedonia Family and Community Enrichment Center, Inc., and entrepreneurship using curriculum from Junior Achievement of Western PA—followed by their choice of two hours of classes at Kulture Dance Academy in McKees Rocks or sports instruction with 5A Elite Youth Empowerment at a nearby park. And that was just before lunch.

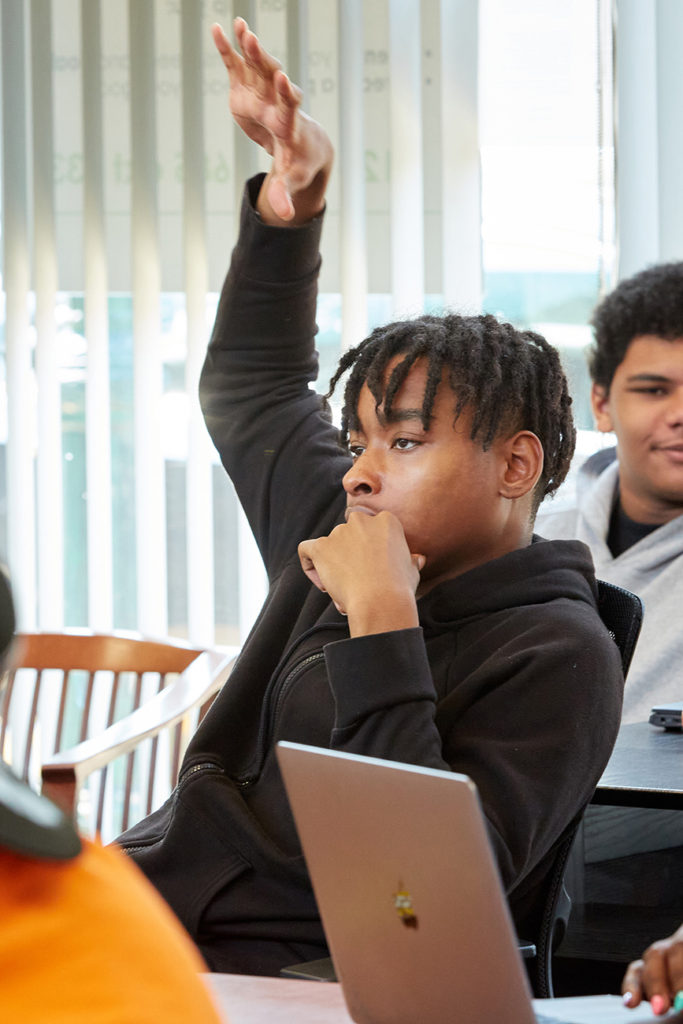

Afternoons were devoted to mindfulness activities and social engagement, with visits to a wave pool once a week. High school students had their own programming, a mix of field trips and a community service project, as well as classes on financial literacy, leadership development, Black cinema, and healthy relationships.

“I had to take a step back and realize they’ve only seen each other online for the past however many months…We had to remind them, there’s a person in front of you. Make eye contact.”

– Keysha Gomez, Executive Director

During the school year, H.O.P.E. for Tomorrow partners with community engagement officers from the Pittsburgh Bureau of Police, who have held cooking classes for children, tutored, played games with them, and taught sports. The officers also showed up for Camp H.O.P.E., including accompanying the younger campers on day trips to Camp Guyasuta, operated by the Boy Scouts of America, Laurel Highlands Council. Older boys who had signed up for Scouts spent five days at the camp, for activities such as swimming, hiking, and archery.

At the beginning, Gomez says the effects of the past year’s social isolation were stark. While many children were returning campers, “It was an eerie feeling when they walked in and just kind of looked at each other” as if they didn’t remember their friends. “I had to take a step back and realize they’ve only seen each other online for the past however many months,” she says. “We had to remind them, there’s a person in front of you. Make eye contact.” After a few days, she saw their brains, emotions, and bodies “warm up.” By week two, parents who’d been arriving early for pick-up didn’t come until five o’clock. “The kids were telling them, ‘Sit outside and wait for us until the very last minute. We don’t want to go,’” she says.

Among its funders, the organization won a grant from the Pittsburgh Steelers to operate the camp, but Gomez didn’t have the resources to open a second location for the many children on the waiting list. She also would have made different hiring choices if she’d had more funds. “We were able to get staff who had great backgrounds working with youth,” she says, but she would have liked to hire some certified teachers to address academic gaps.

Still, Gomez takes the long view. The goal of the partnership with the police is to form lasting relationships, rather than a photo op. Camp traditions are passed on deliberately from older to younger campers to foster a sense of belonging and stability. In that spirit, one former camper turned counselor wrote, “I enjoyed my time as a student, however, I appreciate the opportunity that I have had to help the next generation of H.O.P.E. children that will come after me.”

With many children left on the waiting list this summer, they hope to open a second camp location to accommodate interest.

With more funding, H.O.P.E. for Tomorrow wants to hire certified teachers to more deeply address campers' academic needs.

For Gomez, H.O.P.E. for Tomorrow is part of the ongoing effort of a community to strengthen itself. Especially when it comes to their children, “they want more and we’re working together to make more happen,” she says.

How can we continue to use Covid-19 relief funds and resources to support summer learning?