The non-site-based Mother to Son Success Camp used the resources of the city to help students’ personal growth blossom.

- Five-week summer camp for boys aged eight to 14

- 15 boys attended camp this summer, following interest-built programming

- Focused on personal development and delivering organic learning that teaches responsibility

By Faith Schantz, Contributing Writer for A+Schools

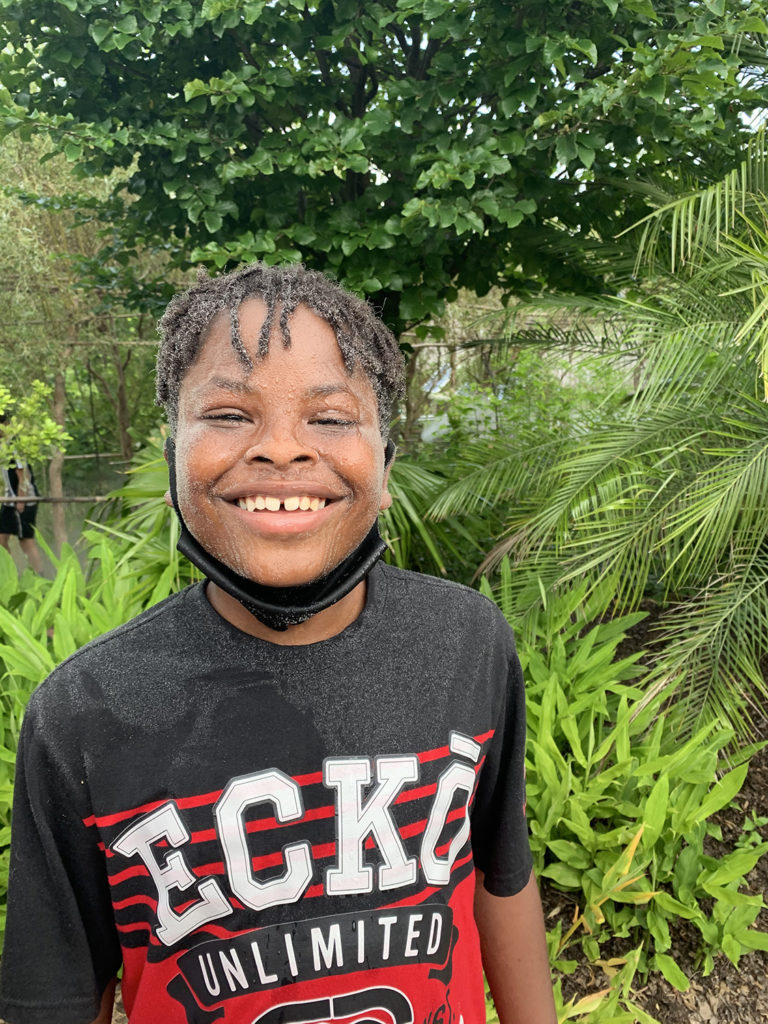

The high rate of single mothers raising children in Pittsburgh prompted the late Dr. James McLemore, pastor of Bethel A.M.E. Church, to found Small Seeds Development, Inc., in 1999. More than 20 years later, the numbers are still high: close to 40% of all families in the city were headed by a single mother in 2019, the US Census shows, compared to less than 25% for the nation overall. For single moms across Allegheny County, East Liberty-based Small Seeds offers a range of support and activities under the umbrella of the “Mother to Son” program. One project is the Mother to Son Success Camp, which served 15 boys aged eight to 14 for five weeks this summer.

For CEO Keino Fitzpatrick, flexibility is paramount. Because the camp lacks its own site, Fitzpatrick builds the program around what is available, using resources such as Tickets for Kids. This year, to meet CDC guidelines for social distancing, he had to reduce the number of campers and find funding to rent an additional van.

The weather also stirred the pot. In the past, he says, “We didn’t have a lot of rain-outs. We were able to conduct camp in a way that was very fulfilling to be outdoors.” This summer, an especially rainy July stranded campers under park pavilions before they could go to another venue, many of which opened later than in the past. In the future, he hopes to secure funding to rent “some sort of indoor shelter area for at least half a day,” he says.

“I didn’t know this existed…I didn’t even know this was there.”

– Campers, on experiencing new spaces & communities

Despite the constraints, Fitzpatrick was committed to providing a camp that the boys would want to attend. In line with family-centered practice, Small Seeds surveys campers and their mothers to identify their interests before deciding what form the program will take. For the 2021 camp, participants asked for music, photography, and time to just “chill out” after the stress of the pandemic.

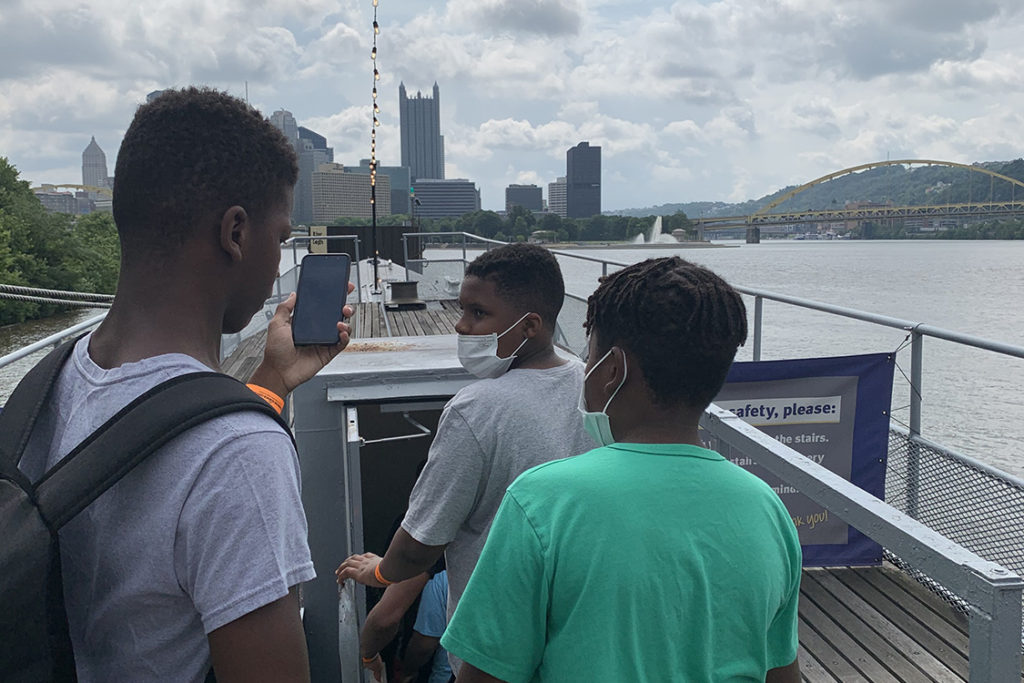

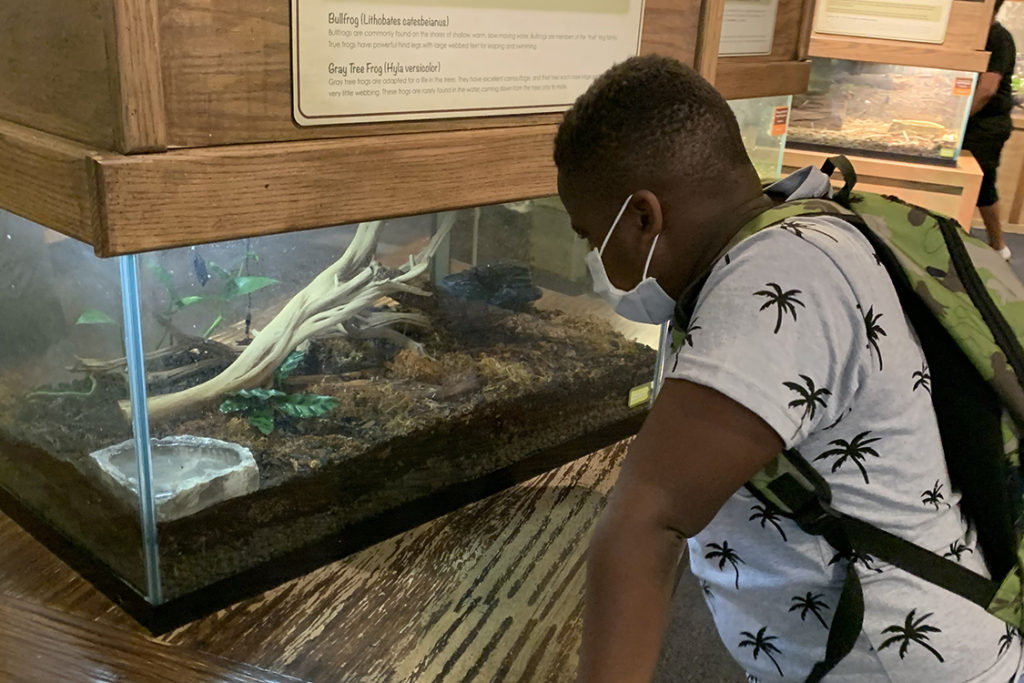

Along with sports, games, and trips to various sites, Fitzpatrick added videography and music production, which involved writing, editing, and saving music on drives the campers could keep. Though it hadn’t been requested, he also included an exercise component for both boys and mothers who’d been forced to be more sedentary during the year.

One advantage of not having a dedicated site is that campers can be “in different areas, spaces, communities they’ve never been in, places that they never experienced,” Fitzpatrick says. Campers who had never ventured beyond their own neighborhoods would say, “I didn’t know this existed... I didn’t even know this was there.” These experiences can produce “a lot of learning that can happen without physically sitting down with them and doing instruction,” learning that is more organic, in his view.

Counselors worked to develop a sense of responsibility in the boys, from remembering to bring their camp-issued book bags each day to looking out for one another. One boy, whose creativity blossomed during the music production component, became “a little bit of a junior instructor,” helping others who didn’t master the equipment as quickly, Fitzpatrick says.

To document such personal growth for the boys themselves and for the organization, the staff administers a survey at the beginning and end of camp. They also send home progress notes, and gather information about how camp is going through “these conversations we're having daily with the moms.”

In the future, Small Seeds Development hopes to secure funding to rent an indoor shelter for a portion of the camp's daily schedule.

On their return to school this fall, Fitzpatrick hopes the boys “would have something to talk about other than, ‘What did you do during the pandemic?'” Instead, his campers could say, “I went to summer camp, I learned this, I was over in this neighborhood, I did these things.” They were still able to “get a life experience,” he says, despite the times.

What if we made more public and private investments in culturally relevant, affirming, and sustaining summer programs for Black and Brown learners, and other learners of color?